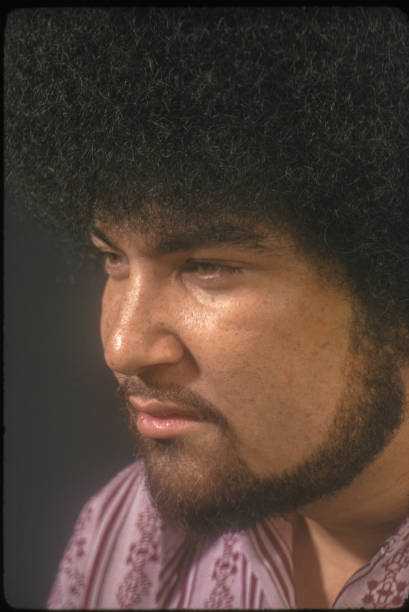

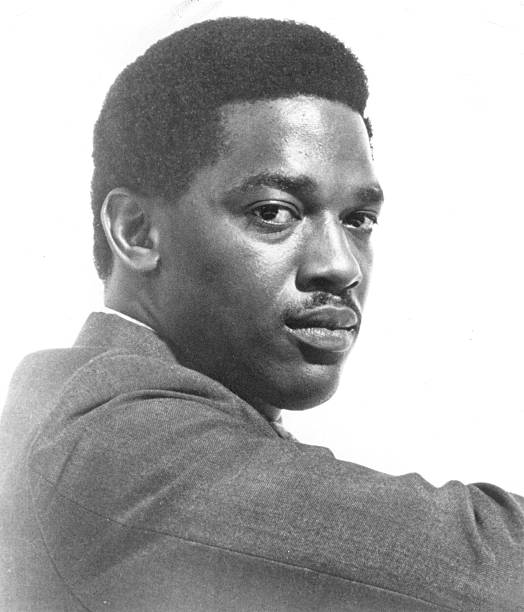

Producer and songwriter Norman Whitfield revolutionized the Motown Sound for a new age in music and culture, eschewing the ebullient R&B grooves that propelled the label’s commercial ascension in pursuit of something much deeper, darker and more daring. Working in partnership with Motown hitmakers like the Temptations and Marvin Gaye, Whitfield drew on contemporary influences including acid rock and funk to create a series of smash singles that explored the triumphs and tragedies shaping Black identity in civil rights-era America, architecting a singularly atmospheric sound retroactively dubbed “psychedelic soul.”

Whitfield joined the Motown Records staff in 1962, a year after the release of the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman,” the first single on the Detroit-based label to reach number one on the Billboard pop chart. The Harlem-born Whitfield arrived in Detroit as a teen: despite limited musical aptitude, he joined future Northern soul legend Richard “Popcorn” Wylie’s Popcorn and the Mohawks, playing tambourine on the group’s lone Motown single, the 1960 novelty “Custer’s Last Stand” (which more prominently featured bassist James Jamerson and guitarist Eddie Willis, both of whom would later play significant roles in Motown history as members of the celebrated Funk Brothers session recording crew).

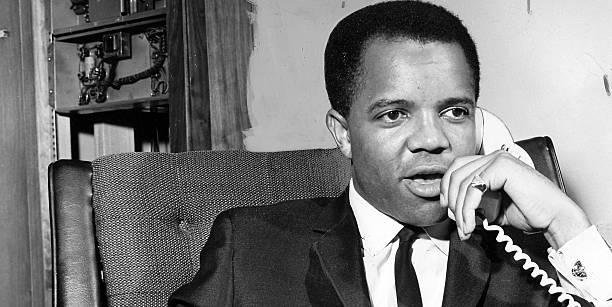

When producer Don Davis founded Thelma Records, he installed Whitfield at the helm of the imprint’s first three singles, attracting the attention of Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr., who recruited Whitfield to join the label as an in-house producer and writer. Gordy immediately paired Whitfield with silky-voiced Marvin Gaye, then a few months removed from his first Top Ten R&B single, “Stubborn Kind of Fellow.” Whitfield, fellow staff producer William ‘Mickey’ Stevenson and Gaye teamed for 1963’s “Pride and Joy,” the singer’s first Top Ten pop hit; from there, Whitfield and Eddie Holland Jr. co-wrote the Marvelettes’ “Too Many Fish in the Sea,” which hit number 25 on the Billboard pop chart in 1964.

With 1964’s “The Girl’s Alright with Me,” the B-side to the Top 40 hit “I’ll Be in Trouble,” Whitfield teamed for the first time with the Temptations, the five-man vocal group that would go on to headline his most innovative and influential Motown productions. The Temptations’ Whitfield-produced “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg,” featuring David Ruffin on lead, heralded a dramatic shift in the group’s sound: while their collaborations with longtime producer Smokey Robinson favored shimmering ballads and velvet-smooth harmonies, Whitfield introduced a dynamic, harder-edged approach indebted to James Brown, whose epochal 1965 single “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” transformed R&B with its two-fisted horns and diamond-sharp rhythms. Whitfield also instructed Ruffin to sing “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” slightly higher than his usual range: isolate Ruffin’s lead here in KORD to fully appreciate the desperation and anguish of the song’s protagonist, a man so adamant his lover cannot leave that he will suffer any humiliation to keep her.

“Norman was a taskmaster in the studio,” Otis Williams of the Temptations told the Detroit Free Press following Whitfield’s death. “He wanted what he wanted. Everybody who worked with him knew he could be very adamant and vocal about what he believed in.”

With “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” the confessional account of a man devastated to learn through the rumor mill of his lover’s infidelity, Whitfield vaulted Gaye to new vocal heights of his own. KORD users should also pay special attention to Whitfield’s simmering production, which is somehow both spacious and claustrophobic at the same time, perfectly conveying the tortured psyche of a man gasping for air and grasping for terra firma as paranoia consumes him. The Funk Brothers ratchet up the tension: James Jamerson’s foreboding bassline is the record’s indelible signature, of course, but Johnny Griffith’s funereal Wurlitzer and Richard “Pistol” Allen’s warlike tom toms are no less essential to the underlying melancholy and menace. (The same goes for Jack Ashford’s tambourine, which slithers like a rattlesnake winding through the Garden of Eden.) Paul Riser’s string arrangement is another marvel: the punctuations of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra serve notice that “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” is an altogether different kind of Motown record, one that is more sophisticated — more frankly adult — than anything the label had previously attempted.

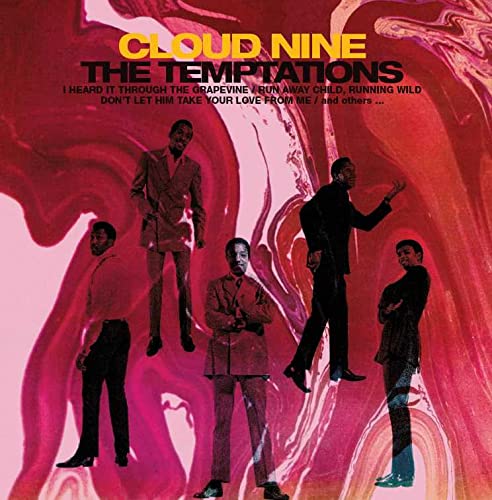

Five days prior to issuing “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” as a single, Motown released another Whitfield landmark: the Temptations’ gritty, provocative “Cloud Nine” — ground zero for the psychedelic soul aesthetic the producer explored and expanded over the duration of his Motown tenure. “Cloud Nine” (co-written by Whitfield and Barrett Strong) took its musical inspiration directly from the trailblazing flower-power funk of Sly and the Family Stone’s 1968 Top Ten pop hit “Dance to the Music” — all five Temptations trade lead vocals (including newest Tempt Dennis Edwards, replacing the increasingly erratic, cocaine-addicted Ruffin) — while its lyrics present an unflinching portrayal of inner-city life, a “dog-eat-dog world” where “it ain’t even safe no more to walk the streets at night.” This brash, muscular approach, complete with lysergic wah-wah guitar from newly-minted Funk Brother Dennis Coffey and the incendiary conga drums of guest percussionist Mongo Santamaria, further redefined the Motown Sound, setting the stage for future masterpieces like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions.

“Cloud Nine” was an unqualified commercial triumph, reaching number two on the R&B chart and number six on the pop chart. The single also won Motown its first-ever Grammy Award in 1969, for Best Rhythm & Blues Group Performance, Vocal or Instrumental. Its success liberated Whitfield from Motown’s assembly line-inspired, hit-factory ethos — a corporate strategy that writers Lenny Kaye and David Dalton called “individual independence subordinated to the needs of a vast, insatiable audience.”

Whitfield produced the entirety of the Temptations’ 11th studio album, 1969’s Puzzle People, which juxtaposes psychedelic-inspired covers of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude” and the Isley Brothers’ ‘It’s Your Thing” alongside originals like “Slave” (a broadside against the injustices of the American prison system) and the Black power anthem “Message From a Black Man.” The LP’s biggest hit, “I Can’t Get Next to You” (another Whitfield/Strong co-write), was on paper its most conventional entry — its clever, colorful spin on unrequited romance would have sailed through Motown’s quality control tribunal at any time in the label’s long history — but Whitfield’s audacious production is a different matter altogether.

“I Can’t Get Next to You” begins with the sound of applause (later sampled in another Whitfield-produced Temptations hit, “Psychedelic Shack”) before Dennis Edwards hushes the audience, entreating them (and us) to “Hold it, hold it, listen.” A bit of late-night barroom piano immediately follows… and then, the Funk Brothers absolutely erupt. Blasts of brass make way for a dazzlingly complex web of percussion dominated by Coffey’s metronomic, chicken-scratch guitar. As for the Tempts themselves, they’ve never sounded so fierce or so focused — it’s another round-robin lead vocal showcase, à la “Cloud Nine,” but as you hear in KORD, “I Can’t Get Next to You” even more vividly spotlights the extraordinary range of their individual voices, ping-ponging from the depths of Paul Williams’ baritone to the preposterous heights of Eddie Kendricks’ falsetto.

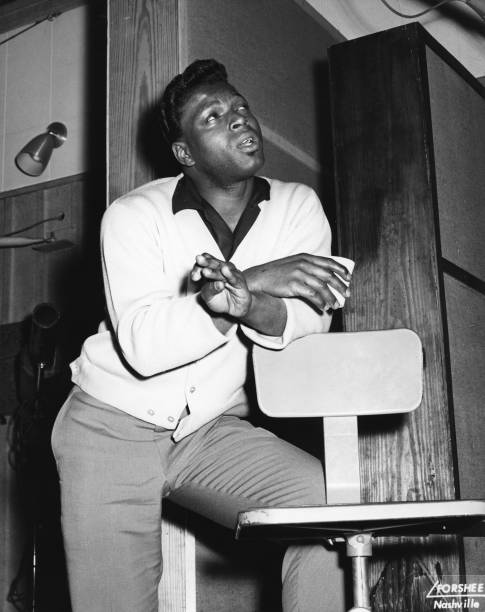

“War,” a scalding diatribe against the conflict in Vietnam, first appeared on the Temptations’ 1970 Psychedelic Shack album, but college students and activists implored Motown to issue it as a single. Whitfield voiced his support, but neither Berry Gordy nor the Temptations themselves wished to jeopardize the group’s image or alienate more conservative audiences, so a compromise was finally reached: Motown would consent to releasing “War” to radio and retail, but only if Whitfield re-recorded the song with another artist. Singer Edwin Starr, at that point two years removed from his lone Motown hit, “Twenty-Five Miles,” raised his hand.

While the Temptations’ rendition of “War” favored an austere approach, Starr’s “War” is a maelstrom — battle-scarred soul music with the apocalyptic anguish of gospel and the thundering intensity of heavy metal, complete with guitar pyrotechnics from the ceaselessly inventive Dennis Coffey. Whitfield and Strong dispense entirely with the familiar tools of the protest anthem trade, like allegory and metaphor: the stakes are too high, the consequences too horrific, to risk anyone mistaking the song’s message. While the immortal chorus (“War! What is it good for? Absolutely nothin’!”) says it all, Starr nevertheless makes the most of clunkier couplets like “War, I despise/’Cause it means destruction of innocent lives,” howling and growling with the unrestrained fervor of a pentecostal preacher — a bravura performance that defined the remainder of his life and career.

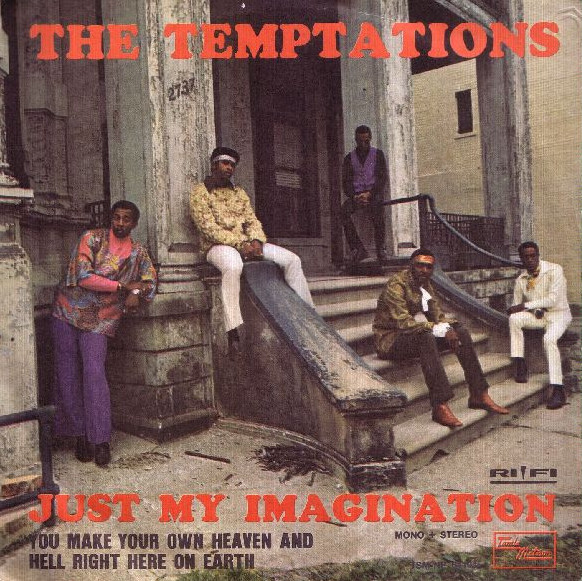

Whitfield followed the most aggressive hit of his career with the dreamiest: the Temptations’ “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)” shimmers and sighs, elevating the everyday pathos of unrequited longing into the realm of sugar-spun fantasy.

While “Just My Imagination” bears the unmistakable hallmarks of a classic Whitfield production — most notably its celestial orchestral arrangement and Funk Brother Bob Babbitt’s gently percolating bassline — the single is also a throwback to the Temptations ballads of yesteryear. Whitfield and Strong in fact wrote “Just My Imagination” in 1969, but shelved it in favor of more ambitious, forward-looking material; following the commercial failure of 1970’s “Ungena Za Ulimwengu (Unite the World),” a psychedelic plea for peace, Whitfield dusted off the song, cut the instrumental track, and recruited arranger Jerry Long and members of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra to record the horns and strings. The Temptations were “totally knocked out” when they heard the finished product, Otis Williams writes in his 1998 memoir, although Kendricks was less charitable, contending in a 1991 interview that by the time “Just My Imagination” materialized, “the fans were screaming bloody murder” over Whitfield’s studio excesses and demanding a return “to what we do best.”

Motown released “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)” in January 1971: the second single issued from the Temptations’ Sky’s the Limit album, it ultimately spent two weeks at number one on the Billboard Pop Singles chart and three weeks atop the R&B Singles chart. Motown planned to release a third single from Sky’s the Limit, an edited version of the 12-minute, mostly instrumental epic “Smiling Faces Sometimes,” but when Kendricks left the group, Whitfield instead opted to re-record the song with his new protégés, the Undisputed Truth.

The Undisputed Truth’s rendition of “Smiling Faces Sometimes,” which runs a tidy 3:16, was among several major R&B hits of the early 1970s to address the disillusionment and dread gripping Black Americans as the promises of the civil rights movement increasingly proved empty and hollow. The song amplifies the paranoia suffusing Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” only this time, the betrayer is not a lover: it’s the system — the white patriarchal society where no one can be trusted, and nothing is what it seems. “Smiling faces sometimes/Pretend to be your friend,” sings the Undisputed Truth’s Joe “Pep” Harris. “Smiling faces show no traces/Of the evil that lurks within.” Listen closely to how Whitfield’s dense, forbidding arrangement further underlines the anxiety — to borrow from an earlier Motown hit, there’s nowhere to run to, baby, and nowhere to hide.

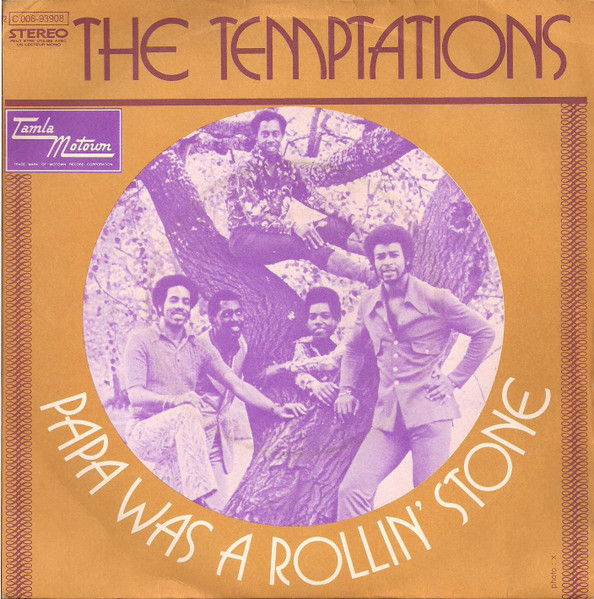

Whitfield’s final and most fearless Motown masterpiece, “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone,” took the opposite route to immortality from “Smiling Faces Sometimes.” This time, the song first appeared in May 1972 as an Undisputed Truth single, but when it peaked at number 63 on the Pop chart and number 24 on the R&B Chart, Whitfield snatched it back, rebuilt it from the ground up, and created a 12-minute psychedelic soul odyssey showcasing the new-look Temptations, whose lineup now featured Damon Harris and Richard Street as replacements for Kendricks and Paul Williams, respectively.

Make no mistake, however: regardless of the name on the label, this is Whitfield’s record — the Temptations don’t even make their presence known until close to four minutes into “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone.” The breathtaking instrumental introduction unspools like a reel of film, its dramatis personae (most notably Babbitt’s throbbing bassline, Aaron “A-Train” Smith’s taut hi-hat, Melvin “Wah-Wah Watson” Ragin’s self-explanatory guitar, and Maurice Davis’ windswept trumpet) entering the frame one by one — an opening sequence as unprecedented and unforgettable as the three-and-a-half minute unbroken tracking shot that commences Orson Welles’ classic film noir Touch of Evil. When the Temptations finally enter stage left, “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” reveals itself in full as another inner-city symphony that brings to a close the cycle “Cloud Nine” started four years earlier, its focus shifting to the disintegration of the family unit. Lead vocalist Dennis Edwards transports us back in time to the death of his father, a man he never knew and never would — a presence defined solely by its absence.

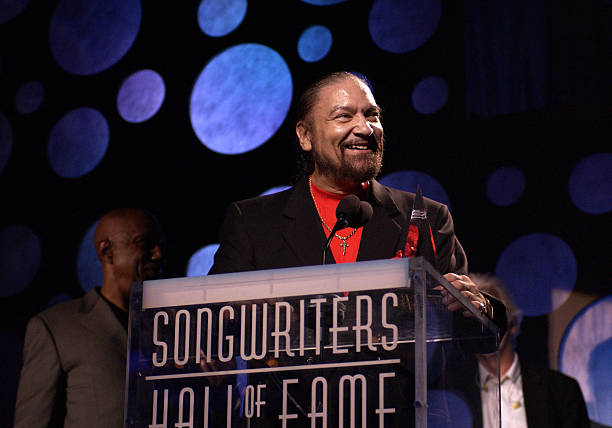

“Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” earned the Temptations their final number one pop hit in addition to winning three Grammy Awards. By this time, however, the relationship between Whitfield and the Temptations was in total freefall: the group reportedly resented the control he exerted over their music, as well as his disinterest in producing the ballads they favored. After the 1973 Temptations album 1990 failed to catch on with audiences or critics, Otis Williams voiced his concerns to Berry Gordy, who installed Jeffrey Bowen to produce their next LP, A Song for You. Whitfield founded his own independent label Whitfield Records soon after, notching an international hit in 1976 with Rose Royce’s “Car Wash” — a disco classic whose sound and success signaled the definitive end of psychedelic soul as a commercial force. He eventually returned to Motown and in 1983 reunited with the Temptations for the single “Sail Away.” Health issues and battles with the Internal Revenue Service derailed Whitfield’s creative momentum in the years to follow, however, and in 2008 he succumbed to complications from diabetes.

“The people make the songs what they are,” Whitfield once said. “As writers, we only do what we do and then we have to give it to the public. They’re the ones who determine if you’re a genius or a failure.”

Related Songs