If you were conceived anytime after the summer of 1973, there’s a good chance you owe your existence to “Let’s Get It On.” Marvin Gaye’s smoldering celebration of libido and liberation possesses an aphrodisiacal power unmatched in the annals of popular music: no song is more universally synonymous with unbridled lust and longing, and no song has soundtracked a greater number of carnal experiences, whether in the real world or in popular culture. But below its surface sensuality, “Let’s Get It On” is as endlessly complicated as sex itself, heralding the culmination of Gaye’s lifelong struggle to reconcile the sacred and the profane — the opposing forces that defined and ultimately destroyed him.

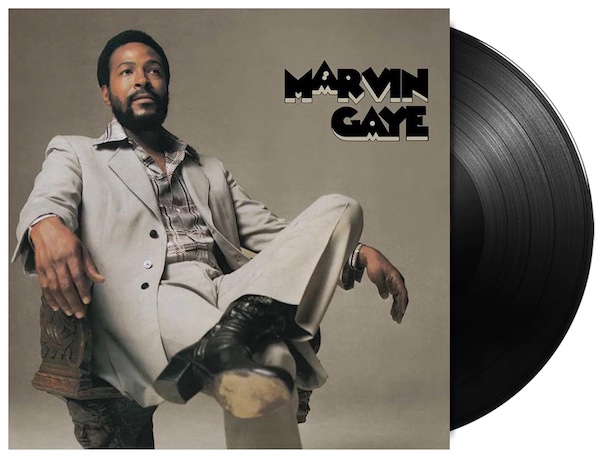

Gaye recorded “Let’s Get It On” in Motown Records’ Hitsville West studio on March 22, 1973, nearly two years after the release of his What’s Going On, the self-produced song cycle that reimagined what music could be. What’s Going On, a profoundly personal and searchingly spiritual album tackling topics including social justice, environmental catastrophe, drug addiction, poverty and war, triumphed over the misgivings of Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. to become the label’s best-selling album to date, setting the stage for auteurist funk masterpieces like Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book. In the aftermath of What’s Going On’s success, Gaye signed a new contract with Motown worth $1 million (equivalent in 2023 purchasing power to about $7.5 million), at that time the most lucrative deal ever signed by a Black artist; however, a planned LP, You’re the Man, was scrapped after Motown declined to promote the title single — a scathing indictment of the U.S. political landscape under President Richard Nixon — over fears it might alienate more conservative audiences.

After completing Trouble Man, the soundtrack to the Blaxploitation film of the same name, Gaye finally began working on What’s Going On’s official follow-up, recording preliminary vocals and instrumentation for the Let’s Get It On album at Detroit’s Golden World Records, known as Motown’s Studio B. When Gordy pulled up stakes and relocated Motown to Los Angeles, Gaye reluctantly followed suit, moving with his family (including wife Anna Gordy, Berry’s sister) to Hollywood, where he teamed with producer and composer Ed Townsend, best known for writing and performing the 1958 R&B hit “For Your Love.” Townsend completed the first draft of what would become “Let’s Get It On” after a stint in rehab; a subsequent rewrite by Motown staffer Kenneth Stover eliminated Townsend’s religious undertones in favor of a more political message, but upon hearing Gaye’s preliminary mix of Stover’s draft, Townsend objected, convincing Gaye the song would be best served as a paean to sexual freedom — a clarion call for spiritual salvation through physical ecstasy.

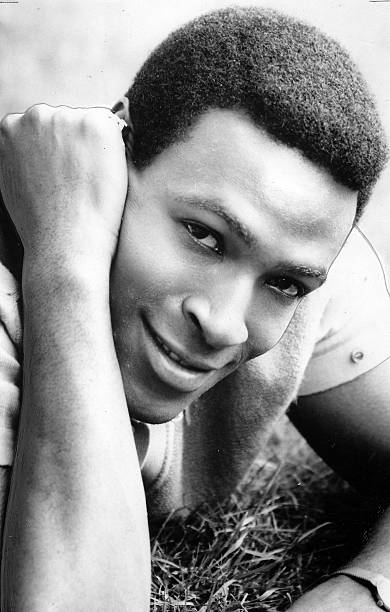

Sex consumed and confounded Gaye throughout his lifetime. As a child he was physically abused by his father, Marvin Gay, Sr., a minister at the House of God, a hardline Apostolic Baptist church that combined elements of Orthodox Judaism and fundamentalist Christianity; Gay Sr. was “a flamboyant and extremely effeminate man,” entertainment industry executive and Gay family neighbor Dewey Hughes told Gaye Jr.’s biographer David Ritz, and his behaviors — including dressing in wife Alberta’s panties and nylons — made the younger Marvin a target of bullies. As an adult, Gaye endured bouts with impotence and grappled with sadomasochistic fantasies, and speculation about his sexual orientation even inspired him to add the “e” to his professional surname (a measure also taken in tribute to one of his idols, soul icon Sam Cooke).

“Feelings of sexual inadequacy permeated the life of Marvin Gaye, Jr.,” Ritz writes in 1985’s Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye. “Complicating matters even more was his father’s sexual ambivalence. Both men saw sex as a dangerous force that threatened and ultimately destroyed their peace of mind and the virtuous life they aspired to lead.” Marvin Gay, Sr. also viewed secular music as a force for evil, expressing enormous contempt for his son’s career and becoming increasingly resentful as Gaye emerged as the family breadwinner — and as his relationship with the long-suffering Alberta grew closer. “A fixation on Mother remained a permanent part of Gaye’s psyche,” adds Ritz, who befriended the singer and interviewed him extensively between 1979 and 1983. “To please, support and protect her was a need and desire that dominated every phase of his life. Marvin measured all other women against Mother, whom he saw as purity and perfection. In his sight, no other woman, save his father’s wife, would ever make him happy.”

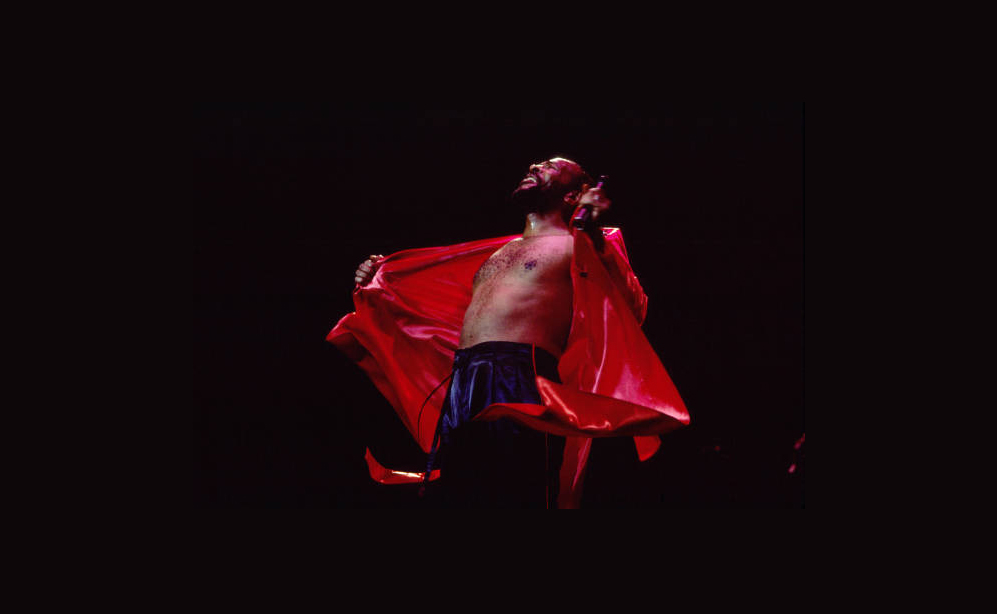

But on the night Gaye recorded “Let’s Get It On,” Janis Hunter entered the equation. Hunter (the daughter of one of Ed Townsend’s friends, jazz vocalist Slim Gaillard) was “the figure in my fantasy come to life, the one I watched dancing round and round in my imagination, whirling from man to man,” Gaye explained to Ritz. “I’d never encountered a more beautiful creature in my life. I had to have her.” Hunter was just 17 at the time, a detail that grows more unsettling as the years pass and casts a dark shadow over all that follows. The impact of her arrival at Hitsville West was nevertheless seismic. “Marvin has been accused of giving only 80 percent of his effort when he sings. His talent allows him to get away with that. Marvin wasn’t a singer who liked to exert himself,” Gaye’s attorney Curtis Shaw told Ritz. “But that night, with Jan listening, he gave a hundred percent. Listen to ‘Let’s Get It On’ and you’ll hear what I’m talking about.” (Even better, you can isolate Gaye’s lead and/or backing vocals here in KORD to hear with unprecedented precision and clarity what the fuss is about.)

When the Let’s Get It On album hit retail on Aug. 28, 1973, 10 weeks after the title cut was released as its lead single, it contained liner notes authored by Gaye himself — a brief manifesto of sorts declaring his independence from the tenets of his father’s faith, in particular the House of God’s insistence on limiting sexual activity to procreation. “I can’t see anything wrong with sex between consenting anybodies. I think we make far too much of it. After all, one’s genitals are just one important part of the magnificent human body,” Gaye writes. “I contend that SEX IS SEX and LOVE IS LOVE. When combined, they work well together, if two people are of about the same mind. But they are really two discrete needs and should be treated as such. Time and space will not permit me to expound further, especially in the area of the psyche. I don’t believe in overly moralistic philosophies. Have your sex, it can be exciting, if you’re lucky. I hope the music that I present here makes you lucky.” Yet “Let’s Get It On” itself contradicts these notes, Ritz contends. “The song concerned the union of love and sex, not their separation. In spite of [Gaye’s] chauvinistic posturing, his art elicited a powerful desire to wed feeling and flesh,” he writes. “The ‘spirit’ to which he referred was holy as well as sexual. Making certain his point was clear, Gaye repeated the word ‘sanctified,’ specifically comparing bodily and religious ecstasy.”

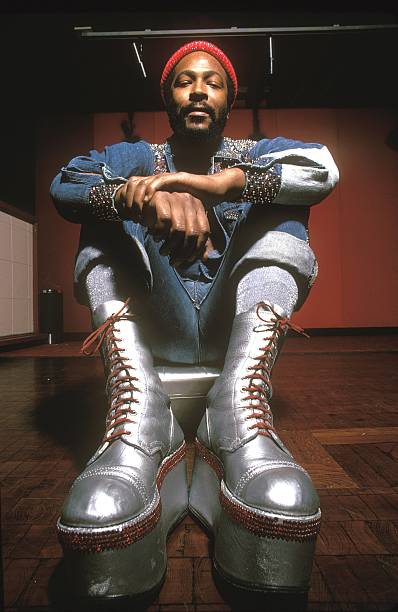

Gaye unleashed “Let’s Get It On” at the tail end of an American sexual revolution that began following World War II, galvanized by the breakthroughs of psychologists and scientists like Wilhelm Reich and Alfred Kinsey. The 1960 introduction of the birth control pill radically transformed the nation’s sexual and social dynamics, enabling women to defer pregnancy and granting them new autonomy over their lives and careers. Landmark books like Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique further challenged traditional gender and sex norms, and the LGBTQ+ rights movement also took shape during this time, bolstered by anti-discrimination demonstrations and protests that climaxed in the Stonewall riots of 1969. Erotic fiction and films entered the mainstream discourse as well, and in 1972, Hugh Hefner’s pioneering men’s magazine Playboy — a longtime Gaye favorite — peaked in circulation at more than 7 million copies worldwide, reaching an audience said to include a quarter of all American male college students. All of which is to say that by the time “Let’s Get It On” materialized at radio on June 15, 1973, less than six months after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling protecting a pregnant woman’s right to an abortion (for the next 49 years, anyway), America was at long last ready for a massive hit record this brazen, this explicit, this intimate: from the deep-shag wah-wah guitar that opens the song, played by session ace Don Peake, to its swoon-worthy strings, to its intoxicatingly slinky rhythms, “Let’s Get It On” seduces you mind, body and soul, establishing the blueprint for quiet-storm classics from Barry White, Teddy Pendergrass, the Isley Brothers and myriad other R&B giants to come.

What’s most remarkable about “Let’s Get It On” is its staying power. The song is as evolutionary as it is revolutionary: in The Descent of Man, published in 1871, Charles Darwin first linked making music to reproductive behavior in the animal kingdom (e.g., birdsong), writing “Musical notes and rhythm were first acquired by the male and female progenitors of mankind for the sake of charming the opposite sex.” Neurologists subsequently determined that sexual-sounding music like “Let’s Get It On” transmits signals to the brain, which registers what you’re hearing as a response to sexual stimulation, then sends a corresponding signal to your genitals, initiating or accelerating sexual arousal. “‘Sex music’ often entails whispering, panting, and moaning that might trigger arousal response in listeners,” clinical psychologist and sex and relationship expert Dr. Nazanin Moali told Remedy Health Media-owned website TheBody in 2022. “Research shows that experiencing other people’s arousal often elevates one’s arousal.” And because sex sells, it has been the dominant subject of popular music for decades, from Ma Rainey’s 1924 dirty blues pearl-clutcher “Shave ‘Em Dry” to Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s hip-hop team-up “WAP,” a number one hit nearly a century later. In fact, approximately 92 percent of the 174 songs that reached the Billboard Top 10 in 2009 contained so-called “reproductive messages,” according to SUNY Albany professor Dawn R. Hobbs’ survey Evolutionary Psychology.

“Let’s Get It On” is in a category of its own, however: you cannot hear it and not think about sex. Beyond its numerous appearances in movies and television (everything from Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me to Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason to The Simpsons), where it’s become something of a shorthand musical cue for an imminent tryst, it remains omnipresent in bedrooms across the globe. In 2012, music psychologist Dr. Daniel Müllensiefen analyzed Spotify user data to identify the songs most likely to appear on playlists curated for romantic encounters, and found “Let’s Get It On” at number two on the list, trailing only Gaye’s 1982 comeback classic “Sexual Healing.”

“Let’s Get It On” proved to be Motown’s biggest U.S. hit to date, moving more than two million copies within its first six weeks and ranking as the second-best selling single of 1973, held out of the top spot by Tony Orlando and Dawn’s “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.” Gaye and Anna Gordy separated by year’s end, and he turned his focus squarely to building a new life with Janis Hunter, the subject of his 1975 album I Want You, which Michael Eric Dyson’s Mercy, Mercy Me: The Art, Loves, and Demons of Marvin Gaye calls “unmistakably a work of romantic and erotic tribute to the woman he deeply loved and would shortly marry.” Gaye and Hunter wed in October 1977, soon after his split from Anna was made official, and divorced in February 1981; Hunter later collaborated with Ritz on a memoir, 2015’s After the Dance, detailing the trauma and abuse she suffered as Gaye’s addictions to sex and drugs worsened. With his relationship with Motown also unraveling, Gaye signed to CBS Records’ Columbia subsidiary to release the acclaimed Midnight Love, scoring his biggest-ever chart hit with the aforementioned “Sexual Healing,” which People magazine dubbed “America’s hottest musical turn-on since Olivia Newton-John demanded we get ‘Physical.’”

At the conclusion of the Midnight Love tour in August 1983, Gaye moved into his parents’ Los Angeles home to nurse his mother back to health from kidney surgery. Marvin Gay, Sr. was absent throughout the first several months of his son’s stay, but upon his return the two men clashed, and struggled to maintain their distance from one another. The situation continued to deteriorate, however, and on the morning of Apr. 1, 1984, the day before his 45th birthday, Gaye intervened in his parents’ argument over a misplaced insurance policy letter, ordering his father out of their bedroom; when Gay, Sr. refused, Gaye reportedly shoved him into the hallway, kicking and punching him. Minutes later, Gay, Sr. entered his son’s bedroom, gripping the Smith & Wesson .38 handgun Gaye gifted him the previous Christmas: two shots were fired, and at approximately 1:01 ET, Gaye was pronounced dead on arrival at LA’s California Hospital Medical Center. Marvin Sr. pleaded no contest to a voluntary manslaughter charge, and received a six-year suspended sentence and five years of probation. “If I could bring him back, I would,” he told the court during his sentencing hearing. “I was afraid of him. I thought I was going to get hurt. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I’m really sorry for everything that happened. I loved him. I wish he could step through this door right now. I’m paying the price now.” Gay, Sr. died of pneumonia in 1998; Alberta Gay, who divorced her husband during his murder trial, died in 1987 after a long battle with bone cancer.

Half a century removed from the release of “Let’s Get It On,” Marvin Gaye’s legacy looms larger than ever. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame enshrined him in 1987, declaring “Gaye’s singing nurtured the soul — both the audience’s and his own,” and in 1996, he received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In addition, Let’s Get It On was inducted into the Grammy Hall Of Fame in 2004, six years after What’s Going On, which in 2020 ranked number one on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. “Like Bird and Billie before him, Marvin Gaye’s death has given him new life. Since his premature demise, interest in his art has blossomed,” Ritz writes in the introduction to an updated edition of Divided Soul published in 1991. “‘He’s our John Lennon,’ Janet Jackson recently told me. ‘The longer he’s gone, the more young people appreciate his contributions. He changed our musical world.’”

Let’s Get It On (KORD-0001)

Related songs: