“Where such men love, they have no desire, and where they desire, they cannot love,” Sigmund Freud wrote in 1925 to illuminate what he famously dubbed the Madonna-whore complex — i.e., the dichotomy between the women a man finds admirable and those he finds sexually desirable, and the schism at the heart of the J. Geils Band’s lone number one hit, 1981’s “Centerfold.”

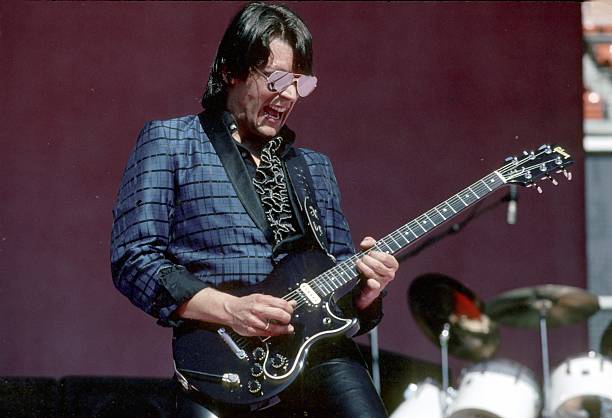

Guitarist John Warren “J.” Geils Jr. formed the group bearing his name in Worcester, Mass. in 1967 with bassist Danny Klein and harmonica/saxophone player Richard “Magic Dick” Salwitz. Originally billed as the J. Geils Blues Band, the trio abandoned its focus on traditional roots music in favor of raucous, good-time R&B with the additions of frontman Peter Wolf (already a local legend as the motor-mouthed overnight disc jockey on Boston FM station WCBN), vocalist/keyboardist Seth Justman and drummer Stephen Jo Bladd. Gigs in support of headliners including B.B. King, Johnny Winter and the Allman Brothers Band cemented the J. Geils Band’s reputation as a force of nature onstage — “Whatever we had in the tank, that tank was gonna be empty at the end of the show,” Justman proclaims in the liner notes for 1993’s Anthology: Houseparty — and in 1970, Atlantic Records released the group’s self-titled debut LP. The Morning After, issued a year later, featured their first Top 40 entry, a cover of the Valentinos’ “Lookin’ for a Love.”

Following Full House, a document of their incendiary live show, the J. Geils Band cracked the Top Ten with 1973’s Bloodshot, highlighted by the swaggering, reggae-inspired “Give It to Me.” But while 1975’s grammar-challenged “Must of Got Lost” climbed all the way to number 12, the group struggled to maintain its commercial foothold, and in the wake of 1977’s Monkey Island (credited to simply “Geils”), it parted ways with Atlantic, signing to EMI Records for 1978’s Sanctuary, which yielded the Top 40 hit “One Last Kiss.”

With 1980’s Love Stinks, the J. Geils Band embraced synthesizers and adopted a more contemporary, New Wave-inspired pop sound, scoring Top 40 entries with the infectious, disco-fied “Come Back” and the sardonic title track. Love Stinks’ sensibilities and success set the stage for the radio-ready Freeze Frame, the group’s tenth studio album but its first, last and only number one.

Freeze Frame, recorded over the better part of a year and released in late 1981, abandoned the blistering R&B covers of previous efforts in favor of nine originals, all penned by Justman either solo or in tandem with Wolf. Justman also produced and arranged Freeze Frame, telling Rolling Stone “We’re really excited about where we’re at now. As a band, as musicians and as people. I think we’ve developed a totally unique sound. Any band that sounds this way now is either the J. Geils Band or somebody who sounds like the J. Geils Band.”

“Centerfold,” the first single from Freeze Frame, lays bare the male psyche to examine the torment of the song’s protagonist, who is scandalized to discover his teenage crush all grown up and featured in the pages of a “girlie magazine.” He is both devastated by her loss of innocence and aroused by the undeniable eroticism of the images before him, a quintessentially Freudian conflict triggered by a breach between the affectionate and sexual currents in male desire. This Madonna-whore complex, which Freud first identified as “psychic impotence,” is said to develop in men who can only control their sexual anxiety by compartmentalizing women as binary opposites: either pure and virginal, or debauched and debased — a dichotomy between “saintly” and “sensual” that animates some of the 20th century’s most analyzed and acclaimed works of fiction, from James Joyce’s 1916 novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece Vertigo.

The Madonna-whore complex remains “highly prevalent in today’s patients,” clinical psychologist Uwe Hartmann wrote in a 2009 article published in The Journal of Sexual Medicine, and it harbors grave consequences. “First, the polarization of this concept forces women to be defined as either a slut or a virgin. This is a gross dehumanization of women — reducing them to their sexual activity denies their personhood and renders them as objects under the male gaze. Women are reduced to their bodies, sexual desirability, capacity or degree of chastity,” writes the University of Pennsylvania’s Rema Bhat in a 2021 op-ed. “Second, in the Madonna–whore complex, female sexuality is viewed as something that is intrinsically degrading and disrespectful. If women choose to partake in sexual activity or posit themselves in a sexual way, they are disrespecting themselves and, by that logic, ought to lose respect in the eyes of others.”

Popular culture plays an enormous role in perpetuating the Madonna-whore complex. The term “centerfold,” given to a publication’s center spread (commonly a foldout of an oversize photograph or feature), was coined by Hugh Hefner, the founder of the pioneering men’s magazine Playboy, which he launched in 1953. Its first centerfold appeared two years later: according to a 1967 TIME magazine cover story spotlighting Playboy’s ascent, an “average though well-endowed girl named Charlene Drain” working for the magazine’s subscription department asked for an Addressograph machine (a tool for printing address labels), and Hefner agreed — provided Drain consented to a nude photoshoot. Because this was 1955, Drain did not sue Hefner for workplace harassment, although she adopted a pseudonym, Janet Pilgrim, when the photos ran in Playboy’s July issue.

The centerfold was soon synonymous with the Playboy brand. “Ever since, the magazine has tried hard to make its girls look ordinary in a wholesome sort of way — just like the Nude Next Door,” TIME explained. “The illusion is heightened by the fact that the girls are presented not only nude and in color, but also in numerous black and white pictures in their natural habitat, whipping up a batch of muffins or playing the guitar. Suggestive poses are out, as are the accouterments of fetishism. None of the nudes ever looks as if she had just indulged in sex, or were about to.”

Playboy isn’t the only American institution propagating the Madonna-whore complex, of course. In mid-1968, around the same time the J. Geils Band ditched its acoustic instruments and went electric, roughly 200 feminists and civil rights activists converged on Atlantic City, N.J. to protest the annual Miss America Pageant, founded in 1921 as a “bathing beauty revue” for single, never-married women between the ages of 18 and 28. A press release issued by the feminist group New York Radical Women, which organized the protest, identified 10 specific points of opposition to the pageant, including “The Unbeatable Madonna-Whore Combination,” noting “Miss America and Playboy’s centerfold are sisters over the skin. To win approval, we must be both sexy and wholesome, delicate but able to cope, demure but titillatingly bitchy. Deviation of any sort brings, we are told, disaster: ‘You won’t get a man!!’”

Although “Centerfold” holds its cards close to its chest, Justman’s deadpan lyrics suggest that his sympathies lie with the “homeroom angel” in the pages of the magazine. The song’s narrator is laughably myopic — his only concern is what the photo spread stirs in him, not what its publication signifies for its subject, the woman he once worshiped. (He’s also shamelessly hypocritical. Not only did he choose to peruse the periodical he professes to find so bloodcurdling, but he purchases a copy, too.)

“Centerfold” is nonetheless too broad and too bouncy to register as social commentary, either then or now: it’s structured like a playground chant, complete with the most irresistible na-na-na vocal refrain to dominate the charts since Steam’s “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” a dozen years earlier, and it’s candy-coated by Wolf’s louche, staccato vocal, Geils’ punchy, power-pop guitar riff and Justman’s immortal opening fanfare, a combination of Prophet 5 and Yamaha CS-80 synthesizers burnished by Magic Dick’s multilayered harmonica.

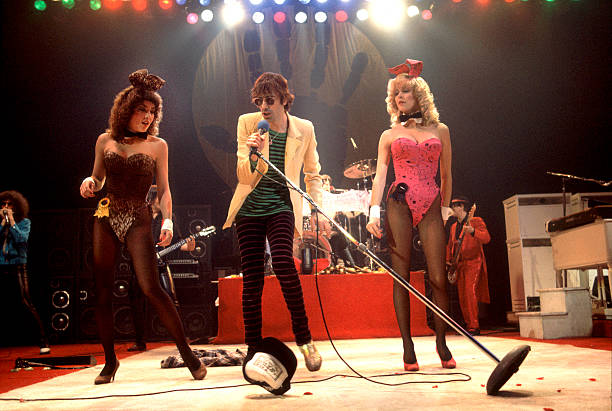

“Centerfold” topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart in February 1982 and held there for six weeks. MTV, which launched six weeks before Freeze Frame reached retail, played an instrumental role in the “Centerfold” juggernaut: the song’s accompanying music video was a fixture of the fledgling cable network’s playlist. The clip, which further muddies the song’s message and intent, features the J. Geils Band performing in a high school classroom, a surprisingly effective setting for the rangy Wolf’s Mick Jagger-esque preening and posing — at least until the negligee-clad coeds take over and render his presence moot.

The J. Geils Band followed “Centerfold” with Freeze Frame’s title cut, which reached number four in Billboard, but Wolf found the group’s increasingly slick, studio-centric identity too confining, and exited for a solo career after the release of the 1982 live album Showtime!, highlighted by an incandescent cover of the Marvelows’ “I Do.” Justman and Bladd split lead vocal duties for the final J. Geils Band album, 1984’s You’re Gettin’ Even While I’m Gettin’ Odd; the group dissolved a year later, but reunited for many live performances and brief tours in the years prior to Geils’ 2017 death.

“I think to see it was to believe it,” Wolf concludes in the Anthology: Houseparty liners. “The J. Geils Band was a real American band — six guys with a love of music, really feeling blessed that we were able to prevail and keep going. We were no frills, no tricks, just hard, sweaty rock and roll. And when we hit the stage, it was showtime.”

Centerfold (KORD-0029)