“Men are what their mothers made them,” Ralph Waldo Emerson famously declared, and with 1968’s Bakersfield Sound bildungsroman “Mama Tried,” Merle Haggard finally came to terms with the man his mother made — not just the transgressions he committed, but also the pleas and prayers he ignored, and the damage that was done.

Haggard lived an extraordinary and quintessentially American life. He was born Apr. 6, 1937 and raised in a converted boxcar in Oildale, Calif., across the Kern River from downtown Bakersfield, the city with which his music is forever associated. His birth trailed two years after the Haggard family abandoned its home in Dust Bowl-devastated East Oklahoma to migrate west, a Depression-era odyssey similar to the one undertaken by the fictional Joad clan in John Steinbeck’s Pultizer-winning 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath. Haggard was just nine years old when his father James, a carpenter for the Santa Fe Railroad, suffered a fatal brain hemorrhage; with his older siblings already in their 20s and living independently, the responsibility for raising Merle fell squarely and solely on 44-year-old Flossie Mae Haggard, a devout member of the ultraconservative Church of Christ. “My mother was left alone when my father died, and she had a good education but had never been able to use it, never been out in the world,” Haggard told Blue Railroad in an interview conducted less than 12 months before his death. “She didn’t know how to drive. She rode a city bus for 27 years and was a bookkeeper at a meat company. And put up with me. I got in trouble a lot. Had too much energy. I wanted to know things.”

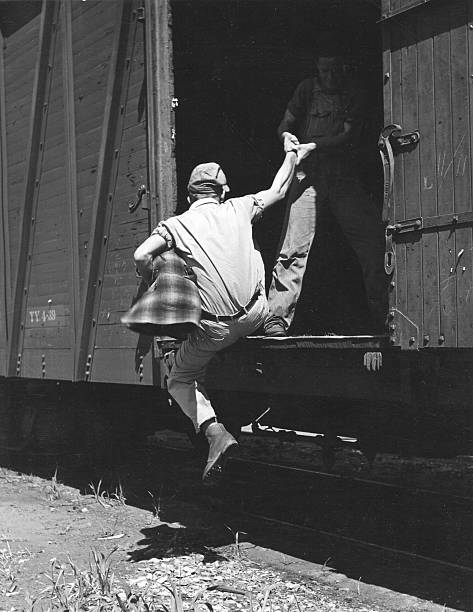

Haggard’s older brother Lowell tried to intervene, passing down his guitar to 12-year-old Merle and taking him to see in concert the Maddox Brothers and Rose (a.k.a. “America’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band”), the pioneering country boogie trio whose sharecropper family fled from Alabama to California in 1933. Haggard soon taught himself to play along with musical heroes like Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzell and Hank Williams, whose recordings he heard via XERB, a 100-kilowatt border radio station broadcasting from Rosarita Beach in Baja, Mexico. His spiral into delinquency continued, however, and in 1950, Haggard was arrested for shoplifting and sent to a juvenile detention center. The following year he and friend Bob Teague ran away to Texas, riding freight trains and hitchhiking back and forth across the Lone Star State; when they finally returned to Bakersfield, they were falsely accused of robbery and briefly sent to jail. Another trip to juvenile detention followed, but this time, Haggard escaped and bolted north to Modesto, where he worked as potato truck driver, short-order cook, hay pitcher and oil well shooter. Haggard also made his public performing debut at a Modesto bar dubbed the Fun Center, singing and playing guitar alongside Teague in exchange for five dollars and free beer.

Haggard was again arrested for truancy and petty larceny upon returning to Bakersfield in 1951; when another stay in juvenile detention culminated in another escape attempt, he was shipped to the Preston School of Industry, a high-security reform school known as The Castle. Haggard was released 15 months later, but sent back to Preston after beating another boy during a burglary attempt. His life appeared to turn a corner in 1953, when Lefty Frizzell played Bakersfield’s Rainbow Gardens dancehall: Haggard and Teague managed to get backstage, where Teague goaded his friend into performing his note-perfect Frizzell impersonation for the honky tonk icon himself. Frizzell was so impressed that he insisted Haggard take the stage and play a couple of songs; singer Billy Mize, who was hosting the performance, took note of Haggard’s talent and invited the 16-year-old to cover Frizzell’s “King Without a Queen” on his syndicated Billy Mize Show — Haggard’s first televised appearance, and the impetus he needed to pursue a life and career making music. He spent the next several years working local farms and oil fields by day while playing Bakersfield bars by night; in 1956, he also married his first wife, Leona Hobbs, with whom he had four children.

Haggard struggled to stay on the straight and narrow, however, and in 1957, he and two friends got drunk and hatched a plan to rob a Bakersfield roadhouse, convincing themselves the establishment would be empty at such a late hour. It was in fact only about 10:30 pm, and when Haggard and his cronies arrived, the roadhouse was still open for business and packed with customers. The men ran away, but they were discovered the next day; police also found the stolen check-printing machine inside Haggard’s car, and he was sent to jail. He once again attempted to escape, and this time it got him transferred to maximum-security San Quentin State Prison. There Haggard learned Leona was expecting another man’s child, and as his psychological condition eroded, he launched an illegal gambling and brewing operation while plotting escape with another prisoner, James “Rabbit” Kendrick. Fellow inmates dissuaded Haggard from seeing the plan through, but Kendrick would not be denied, and in early 1960 he sealed himself inside a packing crate leaving San Quentin for parts unknown. Armed with a 12-gauge shotgun, Kendrick stole a car and managed to rack up 10 additional felony charges in the two weeks he evaded capture; on Feb. 23, he shot and killed a California highway patrolman along a stretch of the mythic Route 66, and when he was finally apprehended and returned to San Quentin, he was convicted of murder and sent to the gas chamber — a denouement that later inspired one of Haggard’s greatest songs, “Sing Me Back Home.” “Even though the crime was brutal and the guy was an incorrigible criminal, it’s a feeling you never forget when you see someone you know make that last walk,” Haggard recalled to Billboard in 1977. “They bring him through the yard, and there’s a guard in front and a guard behind — that’s how you know a death prisoner… That was a strong picture that was left in my mind.”

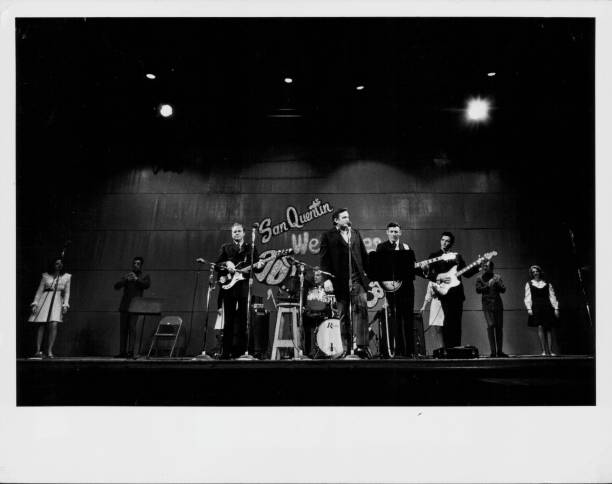

Kendrick’s grim fate — as well as the execution of another notorious San Quentin inmate, Caryl Chessman, the robber, kidnapper and serial rapist known as the Red Light Bandit — inspired Haggard to finally earn his high school equivalency diploma and land a steady job in the prison’s textile plant. Most important of all, he saw a young country singer named Johnny Cash perform no fewer than three times inside San Quentin’s walls. Cash, whose career took flight with the release of the 1955 Sun Records single “Folsom Prison Blues,” regularly played to inmate audiences and throughout his career evangelized for prison reform. “I had been in awe of him since I saw him play on New Year’s Day in 1958 at San Quentin Prison, where I was an inmate,” Haggard told Rolling Stone following Cash’s 2003 death. “He’d lost his voice the night before over in Frisco and wasn’t able to sing very good; I thought he’d had it, but he won over the prisoners. He had the right attitude: he chewed gum, looked arrogant and flipped the bird to the guards — he did everything the prisoners wanted to do. He was a mean mother from the South who was there because he loved us. When he walked away, everyone in that place had become a Johnny Cash fan. There were 5,000 inmates in San Quentin and about 30 guitar players; I was among the top five guitarists in there. The day after Johnny’s show, man, every guitar player in San Quentin was after me to teach them how to play like him.”

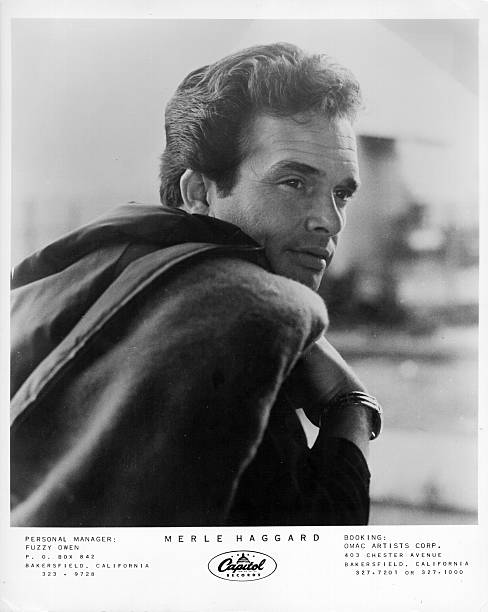

San Quentin paroled Haggard in 1960, and he reacclimated to civilian life by digging ditches for his brother’s electrical company before returning to performing, signing in 1961 to Bakersfield-based Tally Records to release his debut single, the little-noticed “Singing My Heart Out.” Haggard continued touring dive bars up and down the West Coast, and was in 1962 invited to substitute for Wynn Stewart, who was at that time headlining an extended residency in Las Vegas; when Stewart returned to resume the gig, he was so impressed that he invited Haggard to play bass in his backing band.

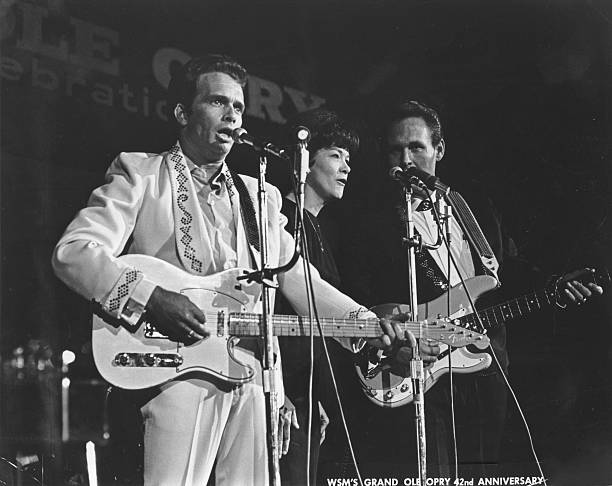

Stewart was the chief architect of the so-called Bakersfield Sound, which evolved in area bars and on local television during the 1950s. The Bakersfield Sound — the musical by-product of the mass migration of “Okies” (like the Maddox Brothers and Rose) to California’s Central Valley — contrasted sharply with the slick, string-sweetened Nashville Sound that dominated national country radio during the latter half of the 1950s: Bakersfield artists like Stewart (and later the iconic Buck Owens) favored a more dynamic, rougher-edged approach incorporating electric instruments and a rock-and-roll backbeat, influencing a generation of artists from the Beatles to the Grateful Dead, who over the decades performed “Mama Tried” in concert more than 300 times. After several months with Stewart’s band, Haggard asked if he could cut Stewart’s “Sing a Sad Song” for Tally; the single climbed to number 19 on the Billboard country chart in early 1964, but although Haggard continued recording for Tally as a solo act, notching his first Top 10 hit with “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers,” he also signed on to play bass in Owens’ legendary backing band the Buckaroos while at the same time entering a romantic relationship with Owens’ ex-wife Bonnie, who was also dating Tally’s co-owner, Fuzzy Owen.

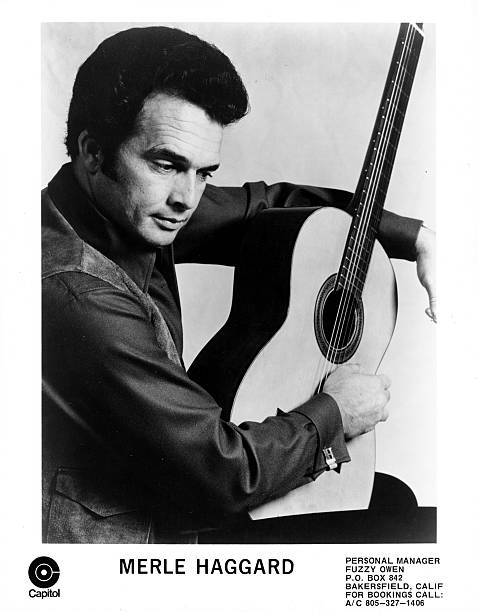

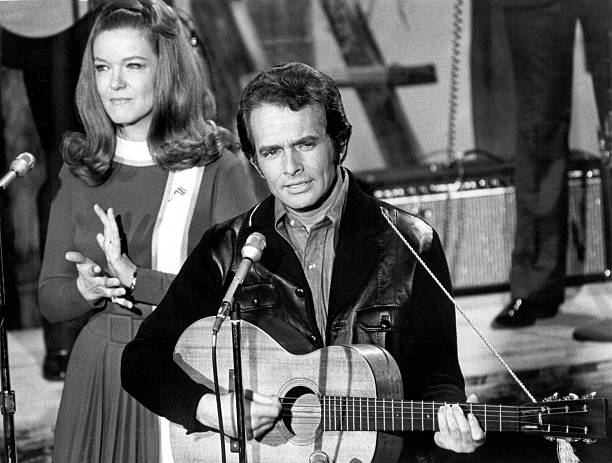

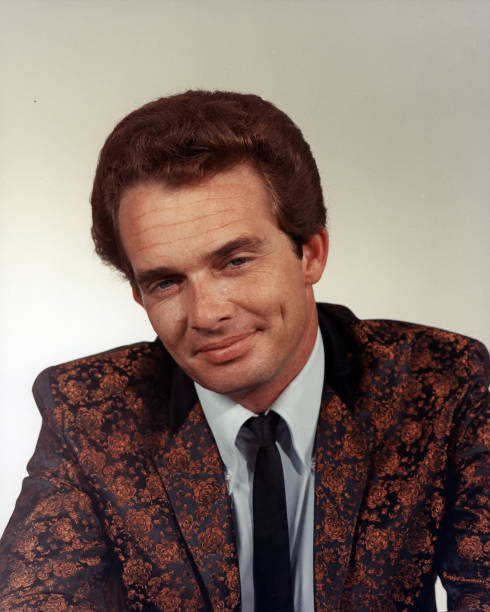

Capitol Records A&R exec Ken Nelson signed both Haggard and Bonnie Owens (soon to become his second wife) at the same time, and on Apr. 27, 1965, Haggard recorded his label debut “I’m Gonna Break Every Heart I Can” at Hollywood’s Capitol Studios. The single failed to crack the country Top 40, and the follow-up, “Shade Tree Fix-It Man,” didn’t chart at all. But with 1966’s “Swinging Doors,” which reached the Top Five, Haggard kickstarted a remarkable run of Capitol singles whose candor and complexity revolutionized country music for generations to come. Landmark recordings like “The Bottle Let Me Down,” “The Fugitive” (his first number one effort) and “Branded Man” — all delivered in Haggard’s nimble, noble baritone and backed by the mighty Strangers (whose revolving ranks at times included former Maddox Brothers and Rose guitarist Roy Nichols, future Elvis Presley guitarist James Burton, pedal steel virtuoso Ralph Mooney and backing vocalist Glen Campbell) — drew liberally on their author’s troubled upbringing to portray blue-collar American life with unmistakable authenticity and unprecedented honesty.

“[Haggard] felt a great deal of humiliation about his past, including the class-based contempt his family faced when he was young (in one of his autobiographies, he comments on their being seen as ‘red-neck Okies’), and the shame he felt about his incarceration,” writes scholar Rachel Rubin in an essay commemorating “Mama Tried” upon its 2015 enshrinement in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry. “Haggard long stated that he tried to hide his prison time until a conversation with Johnny Cash — in which it came out that Haggard was in the audience when Cash famously played at San Quentin Prison — convinced him that he should come forward with his personal history. Not only did he and Cash restage the conversation later on television, but Haggard began to write many very popular songs about incarceration, social rejection and being on the run.”

“Mama Tried,” Haggard’s most accomplished and most autobiographical song to date, was originally written for the 1968 feature film Killers Three, a hicksploitation quickie which cast the singer as a North Carolina state trooper opposite a murderous safecracker played by a mustachioed Dick Clark, the longtime host of television’s American Bandstand, in one of his few dramatic roles. The song is a wayward son’s testament to his widowed mother’s steadfast love, through good times and (mostly) bad — a hellraiser’s resigned lament for the choices he made, and the family name those choices blemished. “Mama Tried” does not appeal for forgiveness, sympathy or even understanding, however; it simply acknowledges that Flossie Mae Haggard did the best she could with the cards she was dealt. “I turned 21 in prison doin’ life without parole/No one could steer me right but Mama tried, Mama tried,” Haggard sings. “Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading, I denied/That leaves only me to blame, ’cause Mama tried.”

“It is true, as in the song, that I was in prison when I was 21. I didn’t get life without parole, though — that’s the only line that isn’t factual,” Haggard told Blue Railroad. “It wasn’t Mama’s fault that I went to prison. She did everything right. She was a wonderful mother: didn’t drink, didn’t smoke. You could depend on her. If you’d been gone three weeks and you showed up, she’d fix you the greatest breakfast you ever had. She was a shy person: when I played her the song, she said the ladies at church would razz her about it. I told her I wanted to buy her a Lincoln with my first royalty payment. She said, ‘The ladies in church will make fun of me if you get me a Lincoln. I want a Dodge Dart.’”

Honesty isn’t the only thing radical about “Mama Tried,” however. The song “is also quite admirable in that it presents a working woman, a mother described as ‘working hours without rest,’” Rubin notes. “Such class-based feminism played a hugely important role in 1960s country music, with Haggard taking it on in multiple songs, including ones in which housework is presented carefully as labor. Other examples from the genre include Loretta Lynn’s 1975 ‘The Pill’ — an early celebration of birth control availability — and Dolly Parton’s 1967 ‘Dumb Blonde,’ which she introduced on her debut album, clearly indicating that self-definition and pushing back at gender-based contempt was a huge part of country’s female empowerment.”

The sound of “Mama Tried” is no less progressive. Although Haggard claimed he was “trying to land somewhere in between Peter, Paul & Mary and Johnny Cash,” Nichols’ blistering electric guitar, Burton’s shimmering dobro and the radiant harmonies of Bonnie Owens and Campbell (by now an established hitmaker in his own right) most closely evoke the Byrds’ country-rock landmark Sweetheart of the Rodeo, recorded at Hollywood’s Columbia Studios at roughly the same time Haggard and the Strangers were cutting the Mama Tried album less than a mile away. “The live echo chamber they had — still have — [at Capitol Studios] was a big part of the Bakersfield Sound,” Haggard told Mix Online. “We worked in both studios there — actually recorded ‘Mama’ in Studio A, the larger room. We had no preference; both were great studios, and each one had access to the echo chambers. Things were done much differently back then. You had three hours to record two or three songs. I’d meet with the Strangers in a coffee shop at nine o’clock to discuss the arrangements; I sort of hummed the songs to them in the shop. As I recall, we recorded ‘Mama’ and ‘Workin’ Man Blues’ in one session, and ‘Today I Started Lovin’ You Again’ and ‘White Line Fever’ in another.”

Capitol released the “Mama Tried” single on July 22, 1968, and within weeks it topped Billboard’s Hot Country Singles chart, spending a month at number one. “‘Mama Tried’ was not just another number one single — it was the song that took Haggard out of the insulated world of country music and into the mainstream consciousness,” writes Deke Dickerson in his liner notes to Omnivore Recordings’ essential Haggard retrospective The Complete ‘60s Capitol Singles. “Like Buck Owens before him, Haggard had somehow tapped into a vein that made Bakersfield country music appealing to the average citizen, who might not otherwise buy a country record. From ‘Mama Tried’ forward, Haggard was no longer a star — he was a superstar.”

Haggard continued breaking new ground in the wake of “Mama Tried,” conquering the charts with the semi-sequel “Hungry Eyes,” the provocative “Okie from Muskogee” (a tongue-in-cheek broadside against counterculture values) and the down-but-not-out “If We Make It Through December,” the latter one of nine consecutive number-one country hits he and the Strangers scored between 1973 and 1976. Haggard even appeared on the cover of TIME magazine on May 6, 1974. He left Capitol for MCA in 1977, the same year he was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, and although his starpower dimmed in the years to follow, he remained an institution, in 2006 receiving a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and in 2010 accepting a Kennedy Center Honor from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in recognition of his lifetime achievement and “outstanding contribution to American culture.” Haggard died on Apr. 6, 2016 (his 79th birthday), less than a year after officials relocated the boxcar where he was raised from Oildale to Bakersfield’s Kern County Museum — an unexpected but fitting destination for a childhood home woven into the tapestry of country music lore.

“I’m proud of the way ‘Mama Tried’ has stayed in people’s minds and hearts, and maybe helped define me,” Haggard told Mix Online in 2009. “Even today, 40 years after it was released, I’ll do a concert and guys will come up and show me tattoos that say ‘Mama Tried.’ They’ll tell me — sometimes with tears in their eyes — how that song captures what they feel about their own mothers. That means a lot to me.”

Mama Tried (KORD-0037)