“War” is a howl of psychic agony — a harrowing, hallucinatory broadside against America’s involvement in the decades-long conflict in Vietnam, and the immense human toll it exacted.

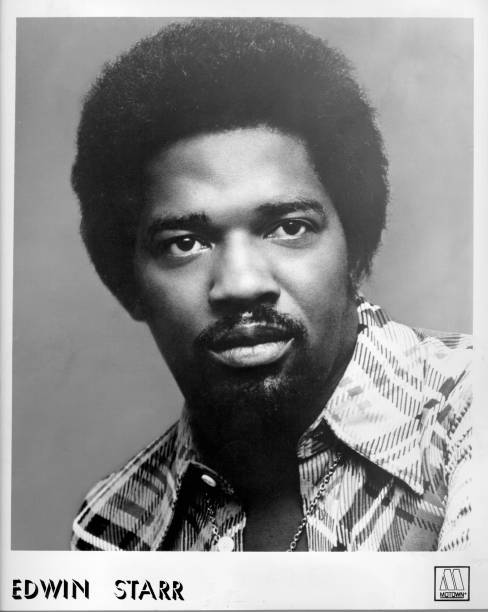

Motown Records unleashed “War” in mid-1970, vaulting to worldwide fame singer Edwin Starr, previously best known for the crossover hit ‘Twenty-Five Miles.” Starr, born Charles Hatcher in Nashville in 1942, first recorded in 1957 as a member of the little-known doo wop group the Future Tones; sometime after the release of their single “Roll On,” he was called to serve in the United States Army, spending the next three years stationed in Europe. Starr eventually returned stateside and resumed his music career, landing in Detroit and signing with local label Ric-Tic Records to cut 1965’s “Agent Double-O-Soul,” a song inspired by the growing popularity of the James Bond film franchise. “Stop Her on Sight (S.O.S.),” written by Starr in partnership with Albert Hamilton and Richard Morris, reached number nine on the Billboard R&B chart in early 1966 and climbed to number 48 on the Hot 100. Ric-Tic’s mounting success so displeased Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. that in 1968 he purchased his crosstown rival for $1 million, acquiring Starr’s contract in the process. But Starr’s career languished under Gordy’s supervision before “Twenty-Five Miles” (a thinly-veiled rewrite of the Jerry Ragovoy/Bert Berns-penned ”32 Miles Out of Waycross”) soared to the number six position on both the pop charts and the R&B charts in early 1969.

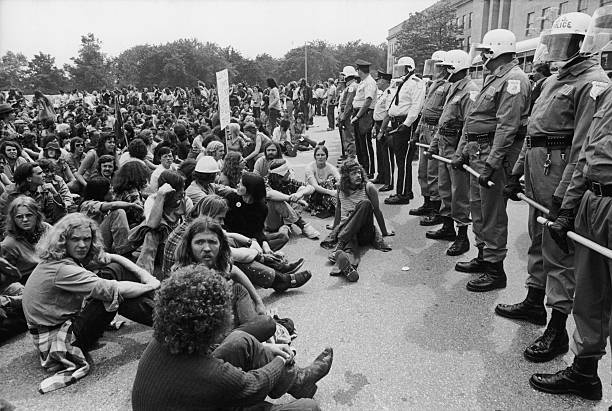

Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong wrote “War” that same year to voice their opposition to ongoing bloodshed in Southeast Asia, where the government of South Vietnam and its principal ally, the United States, squared off against the communist government of North Vietnam and its South Vietnamese allies, known as the Viet Cong. U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War began in late 1955, first in a limited capacity but continuing to escalate until the last remaining American combat troops were withdrawn from battle on March 29, 1973, by which time the conflict had claimed the lives of more than 58,000 U.S. military personnel. Estimates of the numbers of Vietnamese casualties caused by U.S. forces vary, but historians believe between 966,000 and 3 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians lost their lives over the course of the war, which ended on Apr. 30, 1975 with the capture of South Vietnam’s capital, Saigon.

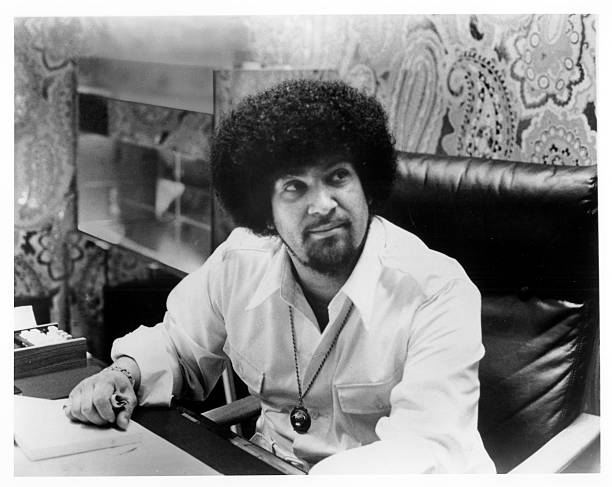

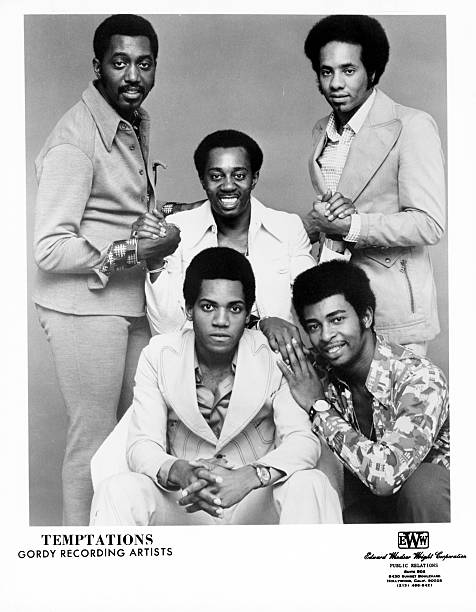

Whitfield and Strong originally penned “War” for the Temptations’ 1970 album Psychedelic Shack. Whitfield, a Motown staffer since 1962, had leveraged his success as the producer of Temptations hits like “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” and “(I Know) I’m Losing You” to develop his own idiosyncratic interpretation of the Motown Sound, a uniquely dark, foreboding aesthetic — retroactively dubbed “psychedelic soul” — that drew on contemporary influences including acid rock and funk to explore the triumphs and tragedies shaping Black identity in civil rights-era America. With the Temptations’ 1968 landmark “Cloud Nine,” an unflinching portrayal of inner-city life whose impoverished protagonist seeks succor in narcotics, Whitfield first steered Motown into the realm of boldface social commentary, a dramatic turnabout for a label that had for years avoided overt political statements. But even though “War” was by no means the first song to directly grapple with Vietnam (that honor goes to the protest singer Phil Ochs’ “Vietnam,” first published in Broadside magazine back in October 1962), its stridently pacifist message was terra incognita for Motown, meaning Gordy flatly resisted calls from college students and activists to release the Temptations’ version as a single, fearing it might jeopardize the group’s image or alienate more conservative audiences. Motown would consent to releasing “War” to radio and retail, however, provided Whitfield re-recorded the song with another artist — one less vital to the label’s bottom line. Starr, at that point a full year removed from the success of “Twenty-Five Miles,” raised his hand.

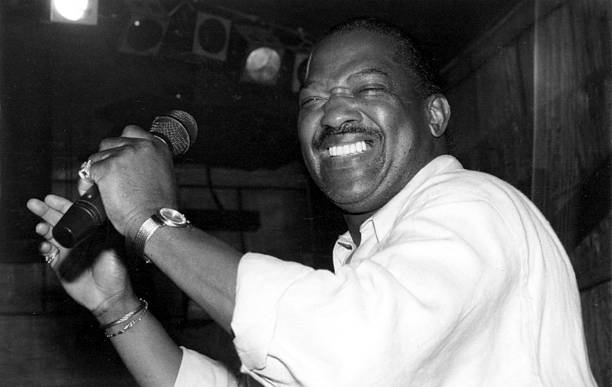

Starr’s interpretation of “War” arrived in lockstep with growing public opposition to the Vietnam crisis. The single was recorded at Motown’s Hitsville USA in May of 1970, 11 days after members of the U.S. National Guard opened fire on anti-war protesters at northeast Ohio’s Kent State University, killing four students and wounding nine others — an event that inspired a nationwide student strike responsible for closing hundreds of colleges and universities, and which H.R. Haldeman, a top aide to President Richard Nixon, later cited as the beginning of the end of the Nixon administration. While the Temptations’ rendition of “War” favored a relatively restrained approach, Starr’s “War,” issued June 9, is an absolute force of nature. Battle-scarred soul music with the apocalyptic anguish of gospel and the thundering intensity of heavy metal (complete with guitar pyrotechnics from the Funk Brothers’ ceaselessly inventive Dennis Coffey), “War” dispenses entirely with the familiar tools of the protest anthem trade, like allegory and metaphor: the stakes are too high, the consequences too horrific, to risk anyone mistaking the song’s message. While the immortal chorus “War! What is it good for? Absolutely nothin’!” says it all (and went on to inspire a Seinfeld plot point), Starr manages to make the most of clunkier couplets like “War, I despise/’Cause it means destruction of innocent lives,” growling and grunting with the unrestrained fervor of a pentecostal preacher — a bravura performance that defined the remainder of his life and career.

“War” topped the Billboard pop chart in August 1970, knocking off Bread’s “Make It with You,” and held at number one for three consecutive weeks, when it was usurped by another Motown release, Diana Ross’ “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” “War” went on to win the Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance, but to his credit, Starr resisted the urge to embrace more commercial, less provocative fare in the years to follow, reuniting with Whitfield for singles like “Stop the War Now” and “Funky Music Sho’ ‘Nuff Turns Me On” as well as the 1971 full-length Involved, which The Village Voice’s Robert Christgau called “Norman Whitfield’s peak production.” Starr left Motown after completing work on the soundtrack to the 1973 Blaxploitation film Hell Up in Harlem but continued recording and touring the U.S. and Europe, scoring a pair of disco-inspired U.K. hits in 1979 with “Contact” and “Happy Radio.” Starr moved to Britain in 1983, and in the decades to follow became a fixture on the Northern soul dance circuit; he also performed at the 2002 wedding of EGOT winner Liza Minnelli and producer David Gest, and was booked for the couple’s first anniversary party — a shindig scrapped after the U.S. military invaded Iraq. Starr suffered a fatal heart attack at his Nottinghamshire home on Apr. 2, 2003; he was 61.

“War” returned to the U.K. pop charts in 1984 when it was covered by British media darlings Frankie Goes to Hollywood as one half of a double-A-sided single, opposite another anti-war salvo, “Two Tribes.” Frankie Goes to Hollywood promoted the single’s release with a lavish marketing campaign, complete with t-shirts reading “Frankie Say WAR! Hide Yourself,” and both “Two Tribes” and “War” also featured on the synth-pop band’s bestselling debut, the two-LP Welcome to the Pleasuredome. Two years later, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band reached the U.S. Top Ten with a live version of “War” recorded in 1985 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and issued as a single to promote the Live/1975–85 box set. Springsteen continued to perform “War” regularly through his 1988 Tunnel of Love Express and Human Rights Now! Tours, but retired it for 11 years until a 1999 concert at Birmingham National Exhibition Centre, where Starr joined him onstage for a one-time duet performance.

More than half a century removed from its release, “War” is “still the definitive message song,” as Starr once proclaimed. “Some people say politics and music don’t mix,” he added. “But I don’t think most people feel that, because two and a half million people bought the record.”

War (KORD-0036)

Related songs: